For those that missed the preceding posts on this topic (book to own: happiness hypothesis, the evolution of the elephant and the rider) or haven’t yet committed their content to memory, allow me to reintroduce some of the key terms and concepts. Our brain understands the world by processing the information received by our senses. These processes can be grouped by whether they are automatic/subconscious or controlled/deliberate. This post will focus on my primary interest: how cognitive processes affect moral judgments. Links:

The automatic system has a long history and has evolved to serve elemental needs linked to survival (e.g., fight/flight, don’t eat the green berries, etc.). The controlled system is a relatively new adaptation, which separates us from (most, if not all) animals, and has evolved to allow humans to make better long-term decisions and expanding their ability to cooperate in large-scale communities. Jonathan Haidt equates the dynamic between the controlled and automatic systems as akin to a rider atop an elephant:

"The automatic system [the elephant] was shaped by natural selection to trigger quick and reliable action, and it includes part of the brain that make us feel pleasure and pain (such as the orbitofrontal cortex) and trigger survival-related motivations (such as the hypothalamus) ... The controlled system, in contrast, is better seen as an advisor. It's a rider placed on the elephant's back to help the elephant make better choices. The rider can see farther into the future, and the rider can learn valuable information by talking to other riders or by reading maps, but the rider cannot order the elephant around against its will."

It would be pleasant to believe that the human brain is a modicum of efficiency – seamlessly switching to and from the elephant (automatic system) and the rider (controlled) based on what is most appropriate. A car runs a red light and starts careening toward you as you walk down the sidewalk? The elephant throws you to the ground before the rider even puts together what’s happened. Deciding your position on a political or social issue? The elephant steps aside to let the rider judge the merits on each side.

This last step, the peaceful transfer of power from the elephant to the rider, is the destructive delusion that will be the subject of this post. The elephant will not go quietly into the night. Or rather – to be less poetic and more precise – the elephant is unable to see when his services are productive (decision to respond to runaway car) and unproductive (decision on complex policy issue). The elephant takes the lead no matter what the issue. So what does the rider do?

When confronted with a moral issue or really any issue that elicits a strong feeling, the rider is relegated to the role of the lawyer for the elephant: "It is the elephant holding the reins, guiding the rider. It is the elephant who decides what is good or bad, beautiful or ugly. Gut feelings, intuitions, and snap judgments happen constantly, and automatically."

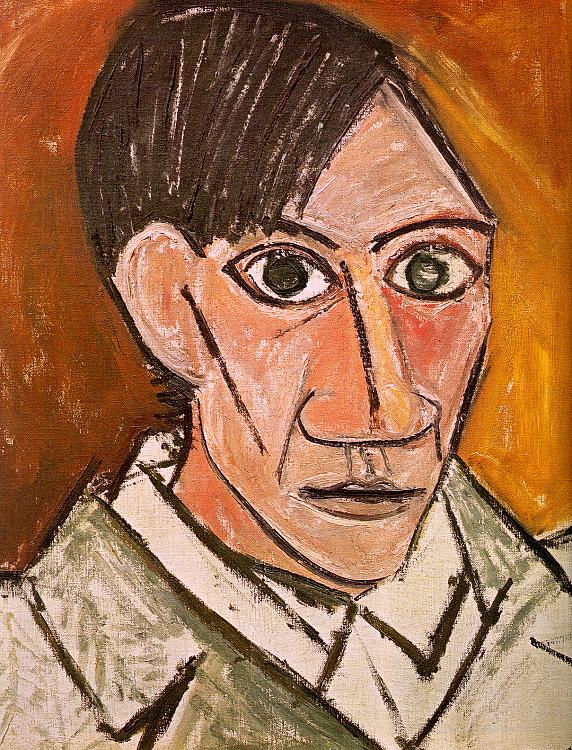

Haidt compares moral judgment to aesthetic judgment: “When you see a painting, you usually know instantly and automatically whether you like it. If someone asks you to explain your judgment, you confabulate. You don't really know why you think something is beautiful."

I think some would disagree that they don’t know why something is beautiful, but I don’t think they would deny the chronology of events:

1. See a Painting

2. Instantly like/dislike the painting

3. Begin to think about why you like/dislike the painting

4. Decide on a reason why you like/dislike the painting

This understanding of moral and aesthetic decision-making is humbling. No one wants to think they are simply confabulating post-hoc explanations for a gut reaction to complex issues like trade agreements or environmental issues. No one really wants to believe that their rider is reduced to "[stringing] sentences together and [creating] arguments to give to other people … fighting in the court of public opinion to persuade others of the elephant's point of view."

Haidt brings up a situation we’re all accustomed to: “When you refute a person's argument, does she generally change her mind and agree with you? Of course not, because the argument you defeated was not the cause of her position; it was made up after the judgment was already made."

It’s quite common to hear people decry “strawmen” arguments. Haidt argues that all of our arguments are (to some degree) strawmen. They are all post-hoc justifications. When "two people feel strongly about an issue, their feelings come first, and their reasons are invented on the fly, to throw at each other.”

To set aside the elephant/rider metaphor, different parts of the brain correspond to different mental activities – the frontal insula is active during “unpleasant emotional states, particularly anger and disgust,” while the “dorsolateral prefrontal cortext, just behind the sides of the forehead, [is] known to be active during reasoning and calculation.” Haidt’s argument merries with my perception that judgments are made in the parts of brain associated with emotion and the subconscious, while the arguments defending the judgments are constructed after the fact in the parts of the brain associated with reasoning and calculation.

The more emotionally detached you are, the more likely the rider can take the reins from the elephant and steer it on a rational, calculated path.

Oomph. I don’t want to dilute this crucial point about how our brains take moral positions and make moral arguments with any additional content. In the next post, I’ll look at how the elephant further muddles our moral judgments by filtering the information that gets to the rider. For now, are there doubts about this theory of making and supporting judgments? If so, I could dig back and supply some of the studies that have looked at brain activity and behavior, which support this understanding, but I don’t want to lose the theory amidst the details if it’s not necessary.

The final post in the series has arrived: man's misuse of morality.

Monday, July 14, 2008

the mind and morality

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

admittedly, i've slept on your blahg.

this is dope though.

Post a Comment