I grew interested in the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (previously the Port Authority of New York) after reading of its role in creating containerports in the The Box, an excellent history of "How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger." I picked up Empire on the Hudson (not recommended) and scoured the internet for information on the bi-state agency. I've quoted from the book below and condensed my learnings to two (free!) blog posts (the second is now up: the decline of the port authority of new york.)

The Port Authority of New York was one of the first government programs designed to be "efficient and nonpolitical ... vigorous and experimental." The agency’s significance does not emanate from its good intentions, however, but from its innovative design, many accomplishments, and gradual decline. Many times before, I have stated the importance of understanding the impact of political economy and organizational design on government program effectiveness. Yet many liberals -who should be the most concerned with a high-functioning government- are ambivalent about the subject, and to no one's surprise, small-government conservatives share this ambivalence. This post will not fill this huge void on its own, but it will provide the first half of a two-part organizational biography of the Port Authority of New York. And to tell the Port Authority's story, we must begin with the history of the port itself.

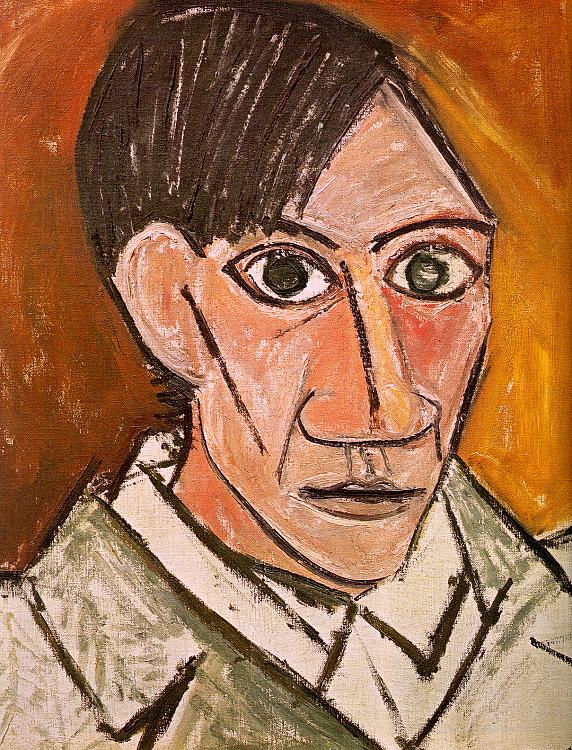

The Port of New York is the United States' largest port, with "nearly 800 miles of waterfront, dwarfing Boston with its 140, Philadelphia with 37, and Baltimore with 120." New York City capitalized on this great natural advantage, with "nearly half of the nation's international commerce - counting both export and import commodities - [passing] through the Port of New York" in 1919. You'll notice in the accompanying image, however, that New York shares the waterway with New Jersey. Yet while New York enjoyed 230 piers at the time, New Jersey had but two.

New Jersey was understandably frustrated by this state of affairs. Its waterfront was actually better oriented for transit, because it was cheaper to ship cargo by rail from New Jersey to the rest of the country than from the island of Manhattan or Brooklyn. However, freight rates were not dictated by actual transportation costs, but set by a government regulatory body, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC). Despite New Jersey's multiple petitions, the ICC maintained that there would be a single rate for rail transit to the Port of New York, whether it was to the New Jersey or New York side, which carried the hidden cost burden of floating freight across the river.

In 1921, New Jersey lost its appeal to the ICC, and New York’s counsel in the case, Julius Henry Cohen, capitalized on the opportunity to win support for a Port Compact, which provided for a bi-state agency to coordinate development for the New York/New Jersey port district. And thus, under the banner of cooperative planning, the Port Authority of New York was born. Each governor would appoint six commissioners to oversee the agency, which would rely "on revenue bonds and user payments (rather than general taxes) to carry out large capital projects," a characteristic unique to the Authority at the time. Furthermore, the Authority worked with the states’ governors to limit local government leaders’ power to disrupt the agency’s plans; a victory for technocratic governance and a (well-deserved) slap in the face of direct democracy.

The autonomous, self-sustaining public agency would largely fail in its initial objective, to resolve the rail problems that had led to the rate discrimination case, but it would leverage its vague prerogative to take on an array of other projects. The Authority’s early years were dominated by bridges, completing the Outerbridge Crossing, Goethals Bridge, Bayonne Bridge, and George Washington Bridge by 1932. The Port Authority wasn’t the first to build bridges, but it managed to build all four bridges under budget and ahead of schedule. A factoid that should make every Boston taxpayer fume. In addition, the agency had beaten out a competing government institution to win control over the Holland Tunnel and its lucrative user fees.

Former New York Governor and then-President Franklin Roosevelt congratulated the Port Authority for its "skill and scientific planning," and celebrated the agency an example for government institutions across America. This praise not only reveals the fantastic reputation the Authority enjoyed in its early years, but also provides the context necessary to understand the agency as the poster child for technocratic progressive government. The Authority’s successes were counted as victories for government-run corporations and cooperation, in contrast to the failure of private firms and dog-eat-dog capitalism. (I’ll return to this subject in the next post).

The Port Authority’s next twenty years were filled with piers and airports. The agency had long lobbied NYC and New Jersey to develop their respective waterfronts, but New York was disinterested in assistance, and Jersey simply couldn’t close the deal. This delay actually ended up working in New Jersey’s favor, however, as by the time the state got its act together in 1955, the shipping container was about to render traditional piers obsolete.

Accordingly, blind luck corrected the ICC’s injustice in the rate discrimination case, with Port Elizabeth leapfrogging its Manhattan and Brooklyn competitors to become the largest containerport in the world. The timing of the waterfront development was a stroke of luck for the Authority as well. The agency had fought hard to construct traditional piers up until the container’s arrival, and only their failre to build the necessary coalition saved them from the embarassment of building infrastructure for the horse-and-buggy of shipping.

In addition to the bridges, the Holland Tunnel, and the containerports, the Port Authority created the Lincoln Tunnel and world’s largest bus and truck terminals downtown, and transformed the Newark, LaGuardia, and JFK airports into the profitable, consumer-driven facilities we know today -- all by 1955.

And there ends the good news. I'l leave the bad news (and the synthesis) for the next post.

Tuesday, February 3, 2009

the rise of the port authority of new york

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment