We've covered the importance of education, and the problems with our current public school education policy. Next up is the university level.

To begin, our universities truly are the envy of the world. That said, we aren't perfect. There are a few low-cost options: community colleges, online degree programs, and technical schools. But these alternatives are generally considered to be "second class" education with a very firm ceiling that rules out many well-paying careers.

In response, progressives have fixated on making it possible for every high school graduate to go full-time to a four-year college.

On one level this makes sense, even marginal college students can expect at least a 7% wage premium per year of college. This is because the bachelor's degree has achieved a majestical stature for students and for employers, signaling (at the least) a basic capacity to be trained (and eventually perform) in a high-value, well-paying profession.

There is nothing inherently wrong with a degree acting as a signaling device; we depend on just such signals for societal trust and exchange.

The problem is that the bachelor's degree is a very expensive signal, and there is reason to believe a very wasteful signal. And while it's not a societal problem if rich people want to spend their money on extravagant signalling, it is a societal problem when our anti-poverty program depends on subsidizing the poor's purchasing of this overpriced signal.

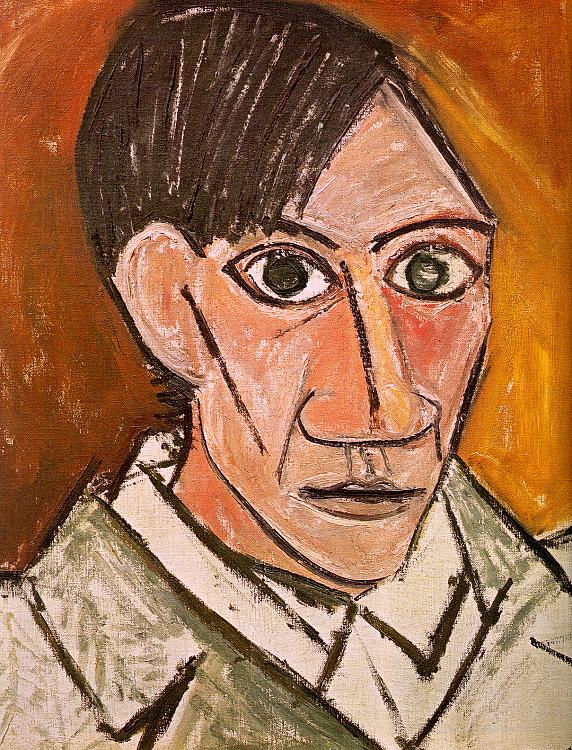

(This is what $60,000 apparently buys you! Apparently, they didn't budget for a decent sense of humor.)

In theory, this problem should resolve itself as firms exploit this opportunity by hiring and training smart high school graduates themselves for less than they would pay the college grads. That is indeed what has happened in India: at least one software company is thriving by hiring young professionals whom others disregard. They don’t look at colleges, degrees or grades, because not everyone in India is able to go to a top-ranked engineering school, but many are smart. The firm goes to poor high schools, and hires kids who are bright but are not going to college due to pressure to start making money right away. They train them, and in nine months, they produce at the level of college grads.

This is not occuring in the US, primarily because of a coordination problem.

Good future workers know they need to go to college to signal their ability to firms and firms know that they have a much higher chance of finding good future workers in the college group. Furthermore, employers are much less likely to have their competence called into question if a hire with a degree doesn’t work out than if they hire a worker without a degree (because of the correct perception of the low likelihood of that hire being a wise choise).

The question is how to credibly signal to good future workers that a four-year college degree isn’t necessary to be considered as a candidate and to convince firms that there are enough good future workers without a four-year college degree to make it a wise investment to include them in their employee search.

The challenge is to develop viable alternatives to the bachelor's degree that don't confer a 'second-class' status. I'd like to see the proliferation of shorter, no-frills academic programs that focus on teaching professional skills and testing relevant capacity (take a lesson from master's programs). In addition, I do believe that CPA-like exams for different professions (or areas of competency) will allow for a more fair and open competition.

There can be great value-added by a four-year liberal arts program, just as there can be value-added by a PHD or masters program; the problem is that the bachelors degree hasn't become an option for those so inclined, but a requirement for a well-paying job - and an expensive requirement at that.

It would be wonderful if we could afford to send every child to a four-year sleepaway camp, where they could sleepwalk through four years of classes (if they so chose) and receive a magic ticket to a well-paying job -- but that isn't the case.

There is a lot of fat to be cut and changes in educational philosophy to be made. Perhaps rethinking the well-manicured campuses and live lectures, for instance. The academic lecture, by the way, has its roots in the medieval training of theologians in a time when one-book-a-course for four years of schooling would cost about $1.6M in book outlays. Back then, it made economic sense to have a lecturer (from latin lector - reader) read from a single book aloud to a hall filled with students. Yet despite the fact that nowadays students could read the contents of a lecture in an instant at virtually no marginal cost, or even watch a video of the lecture -- the lecture remains at the foundation of university teaching.

Everyone in every occupation starts as an apprentice. This is as true of history professors and business executives as of chefs and welders.

The challenge is to make both our advanced schooling and our advanced signaling more efficient and thereby, more accessible. A proper long-term strategy is not to subsidize students' purchasing a $160,000 education, but to support the establishment of alternative means, be it CPA testing or shorter, low-cost advanced degree programs for students to prove their merit to potential employers.

Read more!

Thursday, October 9, 2008

skills to pay the bills - the college years

Wednesday, October 8, 2008

no skills to pay the bills, pt. 1

I'm sure if you asked Barack Obama or John McCain directly about the importance of schools, they'd give you a rousing sermon (or at least a few firm talking points). Yet education reform has been notably absent from our political debate. The candidates love riling up voters' economic nationalism, whether it's talk of foreign oil, foreign cars, China (everyone's favorite boogeyman), outsourcing, globalization, immigrants, or any other buzzword that places blame for American worker woes far from the doorstep of the American government and people.

Yet it’s not globalization or immigration or computers that have widen inequality and slowed wage growth for many Americans. It’s the skills gap.

And while there are plenty of expensive plans to alleviate American poverty to varying degrees, tax-and-redistribution will never provide the economic opportunity and security that we wish for all Americans.

Education should be the primary program to cure our social ills as the key to sustainable high compensation. It is both the key to advancing the welfare of the American poor, and also the means of securing America's economic growth.

This post will focus on primary/secondary education, with a post to follow on college education. Some of the prettier lines from this post I've lifted either from my summaries (linked below) or the original articles (also linked below), but I've spent a bit more time for the sake of flow and coherency to reformulate these ideas.

First, let's recount why education is more important than ever.

The labor market has expanded dramatically in the past 50 years -- undoubtedly for the better of Americans and all mankind. That said, unskilled Americans have had a much, much, much smaller share of the bounty than their fellow citizens.

The problem is that employing unskilled American labor isn't much more profitable than buying a simple machine or employing unskilled labor in a third-world country, yet many unskilled Americans will only accept wages that are much higher than a third-world laborer will accept or a machine will cost.

The value of unskilled labor is low. This sounds like a truism, but it wasn't always the case. Before the machines took over the world and the cost of doing business far from market plummeted, an unskilled laborer simply giving you a few hours time could get a decent wage (of course, that is relative to his peers; relative to his 21st century counterpart his life would be shorter and more brutish). What's more, the American laborer with a high school education likely still had an advantage over his global competition - that advantage has since disappeared.

Meanwhile, unskilled laborers have watched the skyrocketing wages of skilled laborers,. This shift in labor value has been jarring for many Americans, who are ill-prepared to compete for wages based on value-added by their labor, rather than simply time spent at work. And let's be clear, the days of factories full of high-paying manufacturing jobs are gone forever.

Most means of fighting this growing inequality carry large costs that reduce the size of the economic pie (e.g., taxes on capital gains, rent control, large welfare programs). By contrast, investing in human capital encourages work and offers the potential for permanent increases in earnings.

It is no surprise we are seeing a divergence in income when the most valuable skills (soft) are only being attained by a minority of students who graduate college and high-school graduates lack both hard and soft skills.

The skill-wage hierarchy will always exist. Education -increasing skills- is the lone hope for the poor to actually improve their condition.

The wage premium for a high school degree has all but disappeared. There is little point in recounting the soul-crushing underperformance of American public schools, so let us instead look abroad to high-performing examples.

Two of the best primary/secondary schooling examples to learn from reside in Sweden and Finland. The Fins explain the key to their success is to develop excellent initial training for teachers (only ~10% of applicants are accepted for teacher training), start education late and gently (Fins start at 7), and don't waste resources on national testing. The Fins' biggest problem? Getting rid of bad teachers- even with alcohol problems.

While the Fins are more focused on testing achievement (...just not national testing), the Swedes are more interested in developing well-rounded thinkers, evidenced by their varieties of schools and competition, forcing schools to think more pointedly about quality as they risk losing 70k kronor if an unhappy student goes elsewhere.

Swedish reforms in 1994 allowed nearly anyone who satisfies basic standards to open a new school and take in children at the state's expense. Schools can't admit based on religion or entrance exams and nothing additional beyond the set payment by the state can be charged for - but making a profit is fine. Since the reforms, the share of Swedish children educated privately has risen significantly, leading to the proliferation of many "chain" schools.

In these chains, teachers update material on websites, utilize tutors, student-specific syllabi, and weekly student progress reports, and received performance monitoring and bonuses as personal tutors and subject teachers. There are no large school-owned facilities.

The schools are profitable despite only getting a fixed $8-12 thousand per student rate from the locality. The average returns on capital are 5-7% per year thanks to the adept, no-frills, IKEA-style management. I imagine its hard for Americans to imagine so little money can get you student-specific syllabi and tutors - but it can.

Back in the US, efforts to reform public education have centered completely on one thing: money. (One exception is the widely panned NCLB... Why is it panned? Big reason is lack of funding!)

Yet there is scant to any literature that shows increased spending leading to improved results, despite many court decisions mandating increased spending on the premise it is responsible for achievement gaps. That is not to say that less books are as good as more books, but it is to say that spending is not the binding constraint on academic achievement, and that dramatic increases in funding will not lead to the academic gains we'd like to see.

I believe that the public school organizational structure is incompatible with the flexibility and experimentation needed to attain the efficiency and productivity found in Sweden or Finland. Yet until recently, experimentation with other types of schooling has been verbotten. Thankfully, the crumbling public school empire couldn't hold off the barbarians at the gate forever.

Free-market types have managed to carve out a few nooks and crannies for educational experimentation in the US, and we are beginning to see the first efforts to sprout out of these charter-school reservations.

The nation's largest laboratory can be found in New Orleans, where 55% of public school students attend charter schools, by far the highest percentage of any city in the country. Dayton, Ohio and Washington, D.C. are second and third in charter-school market share.

It is still too early to draw firm conclusions on the New Orleans charter system, but there has been demonstrable achievement improvement in what was an entirely stagnant district. Classes are smaller, principals have been reshuffled or removed, school-hours remedial programs have been intensified, and after-school programs to help students increased. Much of the gains are attributed to the quality of instructors.

It would appear that government would be able to accomplish these aims, but it has not. New Orleans charter schools have capitalized on their flexibility to try different programs, allocate resources differently - to innovate. Surely, there will be success and failure in this process; the belief is that the successes will survive and reproduce, while the failures will whither away from disuse.

Top-down government management is ill-suited to support this process.

Meanwhile, in NY, charter schools are experimenting with increased principal autonomy, higher teacher salaries (with cutbacks elsewhere), and other education philosophies. In Washington D.C., there is a pilot program that will pay middle school students that meet academic and behavioral goals.

Are any of these ideas answer? Maybe, maybe not. But whether they work or not, the path to progress in education lies in entrepreneurial districts not national standards, empowered teachers not accredited teachers, and education markets not education mandates. Progressives are often quick to suggest we take notes from top performers around the world. I would love to see us take a page out of the Swedish playbook.

Next, we will look at what's holding back America's university system from reaching its potential.

Read more!

Saturday, June 7, 2008

don't know much biology...

This post will examine the implications of the new economy (see previous post on what's changed here) on education, focusing on the insights of Robert Reich, from his book, The Work of Nations. The broad challenge for the educational system is to transform itself from an ineffectual vestige of the industrial age to meet the needs of the new economy. One of friends who teaches in a NY public school commented that the school system appears to simply exist as a measure of social control. While I don't think this design is deliberate, it does reflect the values - order, discipline, obedience - upon which the educational system is built.

As asserted previously, these values were handsomely rewarded by the old economy. Unfortunately, as the volume-based, assembly-line industrial jobs have disappeared, so has the demand for those values.

Reich identifies four skills that define the value of an individual's labor in the new economy, and thereby, wages: abstraction, system thinking, experimentation and collaboration.

Abstraction: Ability to reduce the infinite parts of reality into simplified mental models, and, in turn, recognize patterns and meanings

System thinking: Understand relationships between various phenomena and underlying processes (e.g., don't simply think about how to solve a problem directly, but why the problem arises and how it's linked to other problems)

Experimentation: Pretty straight forward, but yet poorly taught and understood -- the art of trying out hypothesis, failing/succeeding, analytically assessing results and process of experimentation

Collaboration: Ability to articulate, clarify, restate, critique, and respond to criticism

These skills allow the individual to find unexpected relationships and potential solutions by looking at broader system of processes, variables, and outcomes. Furthermore, these skills empower the individual to hold off his/her natural tendency to view life as static snapshots, which is unfortunately reinforced by compartmentalized subjects like biology, math, etc.

Reich notes that good schools don't ask students to memorize data, but rather present data, and then ask student to assess how/why this particular data is chosen, how it might be contradicted, and, more generally, to critically assess the validity and significance of information in various forms.

Unfortunately, Reich never presents a coherent vision for reforming education because he doesn't see education as the solution to increasing inequality, dismissing the possibility of teaching the children who would become routine producers or interpersonal servers (see past post for more) to become symbolic analysts as "daunting."

While I understand that not every kid can be Einstein, I do think education is *THE* way to improve individuals' abilities to attract higher wages. You can't extort high wages (well, you can, but not forever), and it's the only way to increase individual leverage in the long-term. Furthermore, I think modern-day education is so wildly inefficient and unproductive that we don't truly understand the potential impact of education.

We do know that creative thinking, and problem-solving, is like a muscle, and if it falls into disuse it will atrophy. I often felt that my middle school curriculum killed my creativity, lulling me into an intellectual comatose that I'm only now escaping, and there may be some truth to that.

I will avoid being seduced into an attempt at a holistic take on education reform, but I can't help but offer some brief reflections. First, I think schools are trying to do two different tasks at the same time, and their ability to either suffers because of it. Most straightforward is the desire to impart knowledge and mold young minds. Secondary (?) is the goal of acclimating individuals to interacting with others and building a social acumen. Of course, while we understand that kids will learn more with the guidance of an experienced elder, we somehow think that the best way to socially acclimate these same kids is to let them learn from equally immature and chemically-imbalanced youths.

I think the Ancients really had something with the tutor-pupil relationship afforded to the noble children (except the whole sex thing...). It was understood that learning how to think demanded intense interaction and focus. In addition, social interaction was learned not among emotionally-retarded peers, but with people of vastly different ages and experiences. The Ancients were taught how to be adults. Nowadays, children are taught to be children, and often are taught how to act BY children.

I don't think we can necessarily emulate this example, but I do think it suggests a different role for the teacher and a different dynamic to the classroom. One in which the teacher should be seen a human resources executive, in charge of the development of his/her students. This would include ensuring that top performers receive additional training as well as are given additional responsibility to work with lower performers -- they should be taught to be leaders. In addition, I think it probably doesn't make sense to separate classes by age, and that cross-grade interaction is a good thing for all involved. As a final note, as Reich noted, the breakdown of learning by discrete subjects, like biology or math, is entirely unhelpful for the modern student.

More effort should be placed on teaching students how to think critically, communicate and collaborate effectively, and how to "learn" more generally. The subject matter is secondary to the development of the skills that will allow them to succeed in whatever field they enter. Efforts to stimulate academic interest through "pointless" explorations of sports or popular music are entirely worthwhile if they develop these habits of thinking and learning.

And while I don't want to explore this subject at greater length, I will point my curious readers to this Economist article on education innovations in Finland and Sweden.

Read more!

Tuesday, May 13, 2008

NOLA -- cutting edge of education

Alex Tabarrok over at MR finds some supporting evidence for the advantage and viability of charter schools and school choice in an unexpected place - New Orleans. With little fanfare, Hurricane Katrina's destruction allowed for a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to reinvent public education.”

Alex Tabarrok over at MR finds some supporting evidence for the advantage and viability of charter schools and school choice in an unexpected place - New Orleans. With little fanfare, Hurricane Katrina's destruction allowed for a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to reinvent public education.”

"Stripped of most of its domain and financing, the Orleans Parish School Board fired all 7,500 of its teachers and support staff, effectively breaking the teachers’ union. And the Bush administration stepped in with millions of dollars for the expansion of charter schools—publicly financed but independently run schools that answer to their own boards. The result was the fastest makeover of an urban school system in American history."

The transformation hasn't turned the kids into Einsteins, but there has been demonstrable improvement in what was an entirely stagnant school district.

"Classes are smaller, many of the teachers are youthful imports brought in by groups like Teach for America, principals have been reshuffled or removed, school-hours remedial programs have been intensified, and after-school programs to help students increased... Mr. Vallas attributed many of the improvements in testing to the new teachers. 'The biggest contributing factor was the quality of the instructors,' he said."

A commenter at MR gets at the crux of the issue:

"Smaller classes. Young, energetic teachers. More remedial programs. More after-school programs. Can't government do this? If the answer is no, why not? If the answer is yes, why hasn't it?"

Those are very fair questions for both sides of the private/public debate. I think the government cannot be relied on to do this because education, especially to low-income kids, is too dynamic for top-down management. No Child Left Behind has highlighted the difficulty in top-down accountability, and the low reported results demonstrate that we have not figured out how to relay even the basic concepts needed for success.

There's a lot of experimentation that needs to be done. Teachers and principals need the flexibility to try different programs, allocate resources differently -- in short, to innovate. There will be success and failure in this process.

I think government programs are ill-suited to support this process, as they are vertically-structured organizations that manage local institutions by ensuring they comply with certain processes, curricula, standards of practice, etc. They inherently stifle innovation and create incentives to stick to established practices, even when the established practice is not providing acceptable results to a large number of students.

I don't think it's necessarily impossible for any government managed school to be innovative or successful. The government (likely state level) might introduce market concepts (increase flexibility and accountability for principals, school choice, etc.) into the government-owned system; this artificial environment could certainly be better than what we have now.

Still, the artificial dynamism will never reproduce the dynamism of the actual market. Just as I would rather hire a consultant to teach me how to improve my business, I would rather have a professional, than a bureaucrat, in charge of teaching my kid how to write complete thoughts. If you don't like how they're doing, you can always hire a different one.

Read more!

Thursday, April 10, 2008

How do you hold government accountable?

Via the Economist blog, Ezra Klein wrote about holding the government accountable for its actions:

"There are no benchmarks for success, no metrics that control our troop levels or departure. If al Qaeda is strong and sectarian violence is high, we have to stay and fight. If al Qaeda is weak and sectarian violence is low, we have to stay and protect those gains. It's heads we stay, tails we never leave."

Now, I am going to replace the military/war terms with another government body.

There are no benchmarks for success, no metrics that control our commitment to current education policy or departure. If schools are failing and student scores are low, we have to stay and fight. If schools are succeeding and student scores are high, we have to stay and protect those gains. It's heads we stay, tails we never leave.

Bottom line, liberals want to leave Iraq, and have turned to metrics, or the lack of appropriate metrics to measure improvement or success. What's more, is that the rallying call for Dems has been setting a deadline for the locals to get their act together before we say they are on their own -- despite the immense human cost that would come if they prove less adept at minimizing violence. The conservatives have taken the other side.

Meanwhile, back in the ol' US of A, Dems are decrying the metrics, standards, and deadlines set for public schools and saying we need to double-down on public education and "stay the course." Republicans are flip-flopping right along with the Dems, as tough love suddenly makes sense.

What's the real issue here? Well, on the surface, it's just two parties playing politics with issues of massive importance by whatever means possible.

At the core, however, is a debate about how you best manage government programs. I am not saying you have to think metrics/deadlines/tough love are the answer to education if you think that's the case for Iraq, but I would like to move past the ad-hoc justifications for previously held positions (for/against the war, for/against privatizing education), and focus on the crucial point of contention that applies to both the war in Iraq and education -- how do you hold a government agency accountable when the agency and its supporters are going to say all will be lost if you don't let them continue to work as they see fit, in spite of worsening or improving results.

Of course, one difference between Iraq and public school is that if the US gov't were to leave, it would be easier for the people suffering in public school to leave, while even harder for Iraqis. I'll finish with a tangent link, as Megan McArdle argues the prevention of Iraqi immigration to the US is a mark of national shame; I think she's right of course. If all this talk has you wanting to hear a conservative say they were wrong about Iraq, check out Megan's pretty funny response to an attack from the left, where she admits her mistakes, but clearly hasn't lost her backbone.

Read more!

Tuesday, April 8, 2008

Book to Own: Who's Your City?

A few weeks back, I posted a note on Richard Florida's new book, Who's Your City?, on how the creative economy is making where to live the most important decision of your life. Well, thanks to a Ms. B, I got a hold of a copy. Here are some brief comments from the Amazon reviews before getting to the ideas I found interesting.

The Good and the Bad:

- The spirit of Jane Jacobs lives on.

- The book's tone wanders from broad, Friedmanesque discussion of the world economy to home-buying advice as well as statistic-and-theory-heavy text as though unsure of its intended audience. Yet the author opens up a complex, underexamined subject along the way.

Florida breaks his ideas down into four parts: why place matters, the wealth of place, the geography of happiness, and where we live now. The first two, which comprise 127 pages, contain the meat of Florida's analysis.

Spatial Sorting and its Consequences

Florida begins by deftly dismissing Thomas Friedman's claim that The World is Flat. as he argues for a "spiky world." An important nuisance is that while place matters, it is possible for port cities like NYC and London to integrate considerably; in fact, Florida refers to the pair as NyLon.

He proceeds to explore theories of economic growth before concluding that mega-regions (The Rise of the Mega-Region PDF) are the true economic unit and that they will only continue to grow as creative people and their firms continue to cluster together.

This clustering powers economic growth, but it also has potentially negative byproducts. Florida raises this issue in his discussion of how peoples of greater income and/or ability are more mobile, while those of lesser income and/or ability are more rooted. This phenomena, coupled with gentrification, is leading to a "means migration ... dividing the world into two kinds of regions with very different economic prospects (p. 99)."

He quotes Wharton economist Joseph Gyourko, "This spatial sorting will affect the nature of America as much as the rural-urban migration of the late nineteenth century did," before asking what will happen to American society when city-regions become entirely gentrified, and the poor are relegated to the fringe and beyond.

Finding the right shiny, happy place

The final two parts of the book (170 pages) look at what people look for in a city, where they find it, where specific industries concentrate, and what this means for you in choosing where to live in each of your life stages.

This section of the book is pleasant, but not incredibly thought-provoking, especially as Florida moves away from the city data and toward "make a list of what's important to you!"

Still, I enjoyed finding out about American cities that were getting it right (Fayetteville, Arkansas, really???), and every once in a while Florida would sneak in some insightful commentary that made me glad I didn't skip any chapters.

How Education leads to Sorting...

On p. 247, Florida returns to the idea of spatial sorting. The rich and the creative are clustering in certain mega-regions, and they are also being sorted into mega-regions that specialize in certain industries (finance in NY, music in Nashville, entertainment in LA, biotech in Boston, etc.) The creative power in each of these regions is being amplified by the concentration of talent, but at the expense of diversity (not just racial, but economic, industry, intellectual, etc.)

On the next page, Florida turns to Publius favorite Tyler Cowen to explain society's growing economic divide. The culprit isn't "outsourcing, immigration, or even wage gaps ... the real culprit is the divide in human capital and education."

Cowen: "The return for a college education, in percentage terms, is now about what it was in America's Gilded Age in the late nineteenth century. This drives the current scramble to get into top colleges and universities. In contrast, from 1914 to 1950, the relative return for education fell, mostly because more new college graduates competed for a relatively few top jobs, and that kept top wages from rising too high."

The return on education has "skyrocketed" since 1980, and part of that return is the mobility low-income individuals (like Florida himself) needed to engage the economic opportunities that are not in one's backyard.

Florida jumps back to the subject of education a bit later, as he argues that current schooling was designed for the "old mass-production economy, which no longer reflects the realities of our creative age." Schooling is designed to transmit discipline, not knowledge, and while Florida is careful not to blame the teachers, he argues that schools are squeezing the creativity out of kids.

How Mating leads to Sorting...

People usually marry someone like them in economic/social class. This isn't new, but what is new is the earning power of the women in these relations. As you may have noticed, women are thriving in the workplace like never before.

So, not only is the return on education greatly increased, but now college-educated households are enjoying two times the economic benefits.

All this spells even greater economic inequality. Click here for a wiki chart showing how different percentiles have seen their income rise since 1967. Before I wrap up this beast of a post, I'll add a disclaimer that while Florida has some great insights on economic inequality, it's an incomplete analysis of the American economy and I don't think policy decisions should be based on penalizing top earners for experiencing more income growth than lower percentiles.

A clear lesson from Florida's book, however, is the role of education and its significance in empowering individuals to succeed.

Read more!

Sunday, March 9, 2008

Staying competitive in the global economy

Via The Indian Economy blog, an article in Forbes details the success of an Indian entrepreneur named Sridhar Vembu, the founder and CEO of AdventNet, a software company that is one of the few thriving firms in India producing products (rather than providing services).

What the Chinese have done in manufacturing, he is showing that the Indians can do in software: undercut U.S. and European software makers dramatically.

What's significant is how Vembu has done it.

“We hire young professionals whom others disregard,” Vembu says. “We don’t look at colleges, degrees or grades. Not everyone in India comes from a socio-economic background to get the opportunity to go to a top-ranking engineering school, but many are really smart regardless.

“We even go to poor high schools, and hire those kids who are bright but are not going to college due to pressure to start making money right away,” Vembu continues. “They need to support their families. We train them, and in nine months, they produce at the level of college grads. Their resumes are not as marketable, but I tell you, these kids can code just as well as the rest. Often, better.”

As the United States tries to enhance its competitiveness in the global marketplace, maximizing human capital is key. Vembu has built a $40-million software empire by paying to educate and train the equivalent of high school graduates. Currently, American firms might pay for the graduate training of a promising employee. The Indian experience suggests that American firms should reexamine the utility of the 17-year old. Considering the massive cost of college (and questionable value for job preparation) , many firms might be better off targeting high schoolers directly.

If training and hiring high schoolers is as profitable in the US as it is in India, there could be significant economic and social dividends, enhancing competitiveness by reducing labor costs, while helping restore the promise of economic advancement to a population that has few reasons to keep faith.

Perhaps then Silicon Valley will be losing business to Detroit, and not New Delhi.

Read more!

Friday, March 7, 2008

Beauty of Charter Schools

One of the reasons why I like Bloomberg's education reforms in New York is that it allows for a much greater degree of experimentation, which is good, because I think most would agree that we haven't figured out how to run a school most effectively and efficiently.

A recent New York Times Article, At Charter School, Higher Teacher Pay, detailed plans for a NYC charter school in Washington Heights, which hopes to attract high-quality teachers with a salary of $125,000 and bonus contingent on school performance -- that would double the average NYC public school salary.

The question is "Whether significantly higher pay for teachers is the key to improving schools."

The school’s creator and first principal, Zeke M. Vanderhoek, contends that high salaries will lure the best teachers. He says he wants to put into practice the conclusion reached by a growing body of research: that teacher quality — not star principals, laptop computers or abundant electives — is the crucial ingredient for success.

...