Just wanted to include a brief explanation of the recent addition to the blog -- shared items. Basically, Google Reader allows me to centralize the posts from all the blogs I read, as well as magazine articles, etc. It also allows me to "share" posts/articles I find of particular interest, which I do, and often include a brief note on what I take from the post. It's quick and easy, and fun for the whole family! Read more!

Saturday, May 31, 2008

Friday, May 30, 2008

you thought the miracle fruit was cool...

Man, two articles in one week that completely change what I thought was possible. There was an 'Uncontacted tribe' sighted in Amazon, one of the "few remaining peoples on Earth who have had no contact with the outside world."

Man, two articles in one week that completely change what I thought was possible. There was an 'Uncontacted tribe' sighted in Amazon, one of the "few remaining peoples on Earth who have had no contact with the outside world."

Thursday, May 29, 2008

ammo for liberals

No, I don't mean some juicy rumor about a McCain/Bush romantic romp through Saudi Arabia paid for by stolen welfare funds. This post aims at providing the left with some rational material to work off for criticizing the right and their insistence on market-driven everything. I've come across a blog post that provides some (surprising) insights into health care, which I don't think the people to the right of me would necessarily accept, but I find very interesting and worthy of discussion.

I stumbled across the treatise on health care, via Bryan Caplan over at EconLog, who offered his comments on this supremely interesting recent article on health care in Singapore. Caplan characterizes the Singaporean system as "not laissez-faire, but it is state intervention with the hands of a surgeon."

Caplan then quotes from the piece:

"What’s the reason for Singapore’s success? It’s not government spending. The state, using taxes, funds only about one-fourth of Singapore’s total health costs. Individuals and their employers pay for the rest. In fact, the latest figures show that Singapore’s government spends only $381 (all dollars in this article are U.S.) per capita on health—or one-seventh what the U.S. government spends.

Singapore’s system requires individuals to take responsibility for their own health, and for much of their own spending on medical care. As the Health Ministry puts it, “Patients are expected to co-pay part of their medical expenses and to pay more when they demand a higher level of service. At the same time, government subsidies help to keep basic healthcare affordable.”

The reason the system works so well is that it puts decisions in the hands of patients and doctors rather than of government bureaucrats and insurers. The state’s role is to provide a safety net for the few people unable to save enough to pay their way, to subsidize public hospitals, and to fund preventative health campaigns.

In Singapore’s system, the primary role of government is to require people to save in order to meet medical expenses they don’t expect. While the Singaporean government does regulate prices and services, its hand is nowhere near as heavy as that of governments with extensive nationalized healthcare, such as the United Kingdom or Germany."

Unlike the United States, Singapore features four related, but distinct entities to provide health care. By dividing the health care responsibilities to distinct bodies, Singapore avoids the problem that plagues the American health care market -- trying to accomplish fundamentally different tasks within the same entities: (a) provide everyday care, b) provide insurance for catastrophic unplanned care, c) subsidize care of those who can't afford it, d) subsidized the disabled elderly.

In the US, we try to do it all within the same program, and we do it poorly. Singapore specializes, and is unsurprisingly much better at each task.

1) Medisave: "covers about 85 percent of all Singaporeans, is a component of a mandatory pension program... accounts can be used to pay directly for hospital expenses incurred by an individual or his immediate family."

2) Medishield: "a national insurance plan that covers the higher cost of especially serious illness or accident, which in Singapore’s system is described as “catastrophic.” Singaporeans can choose Medishield or several private alternatives, some offered by firms listed on the Singaporean stock exchange. Premiums for the insurance plans, including Medishield, can be paid using Medisave accounts. "

3) Medifund: "for the roughly 10 percent of Singaporeans who don’t have the means to pay for their medical needs, despite the government’s subsidy of hospital and outpatient costs. The fund was set up in 1993 with $150 million, with the budget surplus providing additional contributions since then. Only interest income, not capital, may be disbursed." (A self-perpetuating financial assistance program, WHAAAAAAAA?!?!?!?)

4) Eldershield: "private insurance for disability as a result of old age. It pays a monthly cash allowance to those unable to perform three or more basic activities of daily living."

It's important to note that patients aren't isolated from price in this system, unlike in the US and Europe:

"Nearly all Singaporeans contribute directly toward each treatment, including prescription drugs, through patient co-payments of 20 percent for amounts above deductible levels. The money to meet deductibles and co-payments can come out of a person’s Medisave account."

A Singaporean health policy professor cites these principles as the source of Singaporean success:

“The creation of incentives for responsible behavior and the efficient delivery of services; the discouragement of overconsumption through cost-sharing; the regulation of hospital beds, doctors, and the use of high-cost medical technology; the promotion of personal responsibility; targeted government subsidies; and the injection of competition through a mix of public- and private-sector providers.”

Does Singapore have all the answers? Definitely not. Check out the article yourself to see Singapore deal with the same issues we are struggling with in the US.

I certainly would prefer a more market-based approach, but if you are more market-averse, Singapore is a much stronger example than France, Cuba, or anything else you'll find in SiCKO. Advocates of the single-payer system should be a bit more discerning in the examples they seek to emulate. I think even most single-payer advocates would admit that the single-payer strategy depends absolutely on intelligent design to work (at all), and simply pointing to the most politically-convenient or recognizable is not a recipe for reform, but simply more of the same.

Read more!

Wednesday, May 28, 2008

tripping on miracle fruits

No, miracle fruit isn't slang for some new street drug, though it should be. The Miracle Fruit, or Synsepalum dulcificum as its known to those in the know, was recently featured in the NY Times. Suffice to say, this fruit blows my mind.

The Miracle Fruit works because of an aptly named protein, Miraculin, which binds to your taste receptors and turns all those sour tastes sweet. This isn't some minor transformation. For one to two hours, you could theoretically drink down battery acid like syrup (though that doesn't sound great either).

More practically, one person interviewed drank Tabasco sauce and said it tasted like donut glaze, and lemons like candy -- mind-blowing.

It works for about 2 hours it seems. You can order them online, though they are pricy.

Given the proliferation of diabetes and other sugar-induced disease, this would seem to indeed be a miracle drug. Unfortunately, the FDA killed that idea about 30 years ago. Why exactly? Haven't looked to see. There are no safety issues I've come across -- it may not be good enough for the FDA, but it's good enough for me.

Read more!

Wednesday, May 21, 2008

one point for social cripples

While searching the internets for results-driven philanthropic efforts, I came across a Wired magazine article by Clive Thompson on "why we can count on geeks to rescue the earth." Thompson is interested in why Gates, "practically a social cripple, and at times he has seemed to lack human empathy" is the "first major humanitarian to take action" against malaria, diarrhea, and parasitic infections, all of which "flew under the radar of philanthropists in the West." "We tend to think that the way to address disease and death is to have more empathy. But maybe that's precisely wrong. Perhaps we should avoid leaders who "feel your pain," because their feelings will crap out at, you know, eight people.

The answer? Gates has been the first to target the world's biggest and most preventable killers not in spite of his social backwardness, but because of it -- "He's also a geek, and geeks are incredibly good at thinking concretely about giant numbers."

Thompson argues that this analytical ability is a particular advantage in philanthropy because of a cognitive failing ingrained in most human beings -- "We are very good at processing the plight of tiny groups of people but horrible at conceptualizing the suffering of large ones.

...

We'll usually race to help a single stranger in dire straits, while ignoring huge numbers of people in precisely the same plight. ... We'll break the bank to save Baby Jessica, but when half of Africa is dying, we're buying iPhones."

This isn't idle speculation. Psychologist Paul Slovic has explored this cognitive failing, including one experiment in which "people were asked to donate money to help a dying child. When a second set of subjects was asked to donate to a group of eight children dying of the same cause, the average donation was 50 percent lower."

Gates' ability to think concretely about big numbers enables him to "truly understand mass disease in Africa. We look at the huge numbers and go numb. Gates looks at them and runs the moral algorithm: Preventable death = bad; preventable death x 1 million people = 1 million times as bad."

Thompson concludes his piece:

That is a terrific advantage if you actually can "understand what a million means" -- I can't -- but I think Thompson is ignoring the power of being aware of that cognitive failing. Your instinct is likely to turn out of a skid, but once you are aware of that instinct and its negative repercussions, you can alter your behavior through purposeful thinking to create a better end.

Overall, I am happy to find an article exploring the negative effect of cognitive bias on philanthropy. I am researching the world of philanthropy in hopes of identifying low-hanging fruit (such as malaria, diarrhea, infectious disease) that take only a little investment for a large payoff.

What is interesting is that early results would suggest the problem isn't necessarily a lack of available philanthropic capital, but a fragmented market of NGOs with unclear objectives, little accountability, and varying visibility.

The answer might not be more money, but structural changes to the way NGOs execute the business of doing good. We'll see.

Read more!

poor and huddled masses

Kevin Mawae is sick and tired of being confined to the lower class. He's worked for 15 years in a gritty industry and is tired of watching flashy prodigies get huge salaries that he could only dream of, despite being among the best at his job. Like most people in that situation, he wants to do something about it. He wants to limit the salaries and bonuses of that higher strata of workers. As it is, the current system of financial reward simply isn't fair in the mind of Mr. Mawae.

The catch?

Mawae is an offensive lineman for the New York Jets, and in 2002 made more than $9 million as the highest paid offensive lineman in the league. Yet the aforementioned sentiments are very real -- Mawae is upset with the contracts first-round picks are getting nowadays, specifically BC alum Matt Ryan's six-year, $72 million deal.

"I know there is sentiment around the league amongst the players like, 'Let's do something to control these salaries and control these signing bonuses' and things like that," said Mawae.

I'm reminded of a quote from P.J. O'Rourke that Greg Mankiw recently cited:

"I have a 10 year old at home, and she is always saying, “That’s not fair.” When she says that, I say, “Honey, you’re cute; that’s not fair. Your family is pretty well off; that’s not fair. You were born in America; that’s not fair. Honey, you had better pray to God that things don’t start getting fair for you.”

I think there is something telling in Mawae's reaction to the Ryan contract. He wants fairness, but his conception of fairness extends only so far as he would benefit. You don't see Mawae admitting that his salary should be controlled to better serve fairness.

The consultant who's watching the Jets in the stands feels the same way about rookie contracts as Mawae, but not simply about rookie contracts, but Mawae's contract as well.

The low-skilled worker feels the same way as the consultant, but not simply about football contracts, but about the prosperity enjoyed by college graduates as well.

Of course, like Mawae, the low-skilled worker may be treated "unfairly" relative to some, but if he were to be treated fairly along with low-skilled people all over the world, he would not like the result.

I think this story is helpful for the greater discussion of poverty. Liberals still stick to their guns with "relative poverty" indicators, so that a person in the US with a car and a microwave is labeled "poor," the same as if he had malnutrition and a life expectancy of 40 years in a developing country living on less than a dollar a day.

The Mawae story is relevant because it demonstrates that there is no magic dollar figure when an individual ceases to believe he is not being rewarded fairly; pursuing the end of relative poverty is chasing a ghost. If we could somehow snap our fingers and the world's citizens were paid like NFL players, people would still think there were significant "relative poverty" wrongs that must be righted.

In this worldview, lowering the well-being of others, the redistribution of poverty, is a victory. When Mawae goes to the bargaining table with the owners, he has stated he will look to stop these high rookie salaries. Will he benefit at all? Likely not, it will simply mean more money for the owners.

When it comes to millionaire football players, who cares if they screw the pooch. The problem is when this same attitude leads individuals to throw away large pieces of the general economic pie because of petty jealousy and envy. The socially just shouldn't be trying to turn princes into paupers in the name of relative-poverty justice. Justice isn't relative.

Update: How does this relative poverty argument play out in the real world? Consider this article, Has Ireland’s Rising Tide Benefited Its Poor? Within, Lane Kenworthy explains how poverty is "on the rise" in Ireland according to standard indicators, despite the fact that the poorest Irish are better off now than they have ever been. Kenworthy offers a worthy substitute for the current relative poverty indicators -- income at the tenth percentile of income distribution; in other words, how much better or worse off are the lowest 10% of income-earners in a given area. Given this indicator, Mawae, the low-skilled worker, and the Irish would all see that their well-being has improved greatly over the past 10-20 years, even as "relative poverty" has grown, allowing us to focus our attention on the genuinely poor and huddled masses.

Read more!

learning from jane jacobs: the poverty trap

Paul Collier, author of The Bottom Billion, and Jane Jacobs, author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, are both careful to differentiate between slums and low-income areas. While Collier and Jacobs' focuses of study differ (far-away nation-states vs. local ghettos) , they both arrive at the same conclusion -- certain geographic areas are caught in poverty traps that prevent the people therein from enjoying any improvement in well-being or opportunity without moving out. Unfortunately, I have only sparse, disjointed notes from the Collier book at the moment (a mistake I must rectify...), so this post will focus on Jacobs. And while I probably should ignore the easy Thomas Friedman diss, I can't help myself -- once again, the world is not flat, geography is still very important to billions of people.

Jacobs describes the American slum as "a human catch-pool ... that breeds social ills and requires endless outside assistance." Slums are notable by their "stagnation and dullness" and "[failure] to draw newcomers by choice."

Jacobs defines a slum as "an area which 'because of the nature of its social environment can be proved to create problems and pathologies,'" which is different than "'a stable, low-rent area.'" The difference is that citizens are able to "make and carry out their own plans right there" in low-rent areas, but not slums. Low-rent areas help their denizens improve their lot in life, and generally eventually become higher-rent areas, not so in slums.

In slums, high-achieving families are driven out (perhaps because of the unsafe streets, lack of available financing for low-income areas, etc.), acting to reverse natural selection for slums. Herein lies the poverty trap at work -- a negative feedback loop that prevents the area from enjoying the positive externalities of economic development.

I'm reminded of a shallow pool of standing water, breeding disease and poisoning those who drink from it. Except most pools evaporate or are washed away; in the slum, the forces that would purify the water source through dilution or some other manner simply leave -- the pool persists.

Part of this negative feedback loop is the lack of social fabric, which only gets worse over time as more and more people act without accountability. Normal state policing can never reproduce the social control a community needs, the community itself must (and indeed the non-slum does) provide a check on illicit behavior, generally without anyone noticing they are a part of this self-policing effort. No such internal check exists in slums. In fact, the opposite occurs; the city continues to act as a conduit for its denizens to cooperate, but to destructive, rather than productive ends. The narc, rather than the drug dealer, gets ratted out.

What are the constraints that trap slums? The most glaring is safety. Just as commerce across the seas has depended on safe seas, so does city commerce depend on safe streets. The analogy extends even further; just as sea trade amounts to a competition between productive forces of exchange and destructive forces of extortion for dominance, so does street life.

The productive forces (often taking the form of bodega owners or other local shops) must make the streets "lively enough to be able to enjoy city public life and sidewalk safety." Jacobs argues the key is to generate productive activity through the stimulation of commerce and cross-use to tip the balance of local power in favor of those who desire peace and commerce. The competition is complex, and the failure of good men and women in slums is a reflection less of their intention or ability than it is of the greater failure to comprehend the specific constraints that are preventing a community from concentrating productive individuals (e.g., is it isolated from the productive outsiders needed for development, does low-income housing push individuals out of the community who reach a certain level of success, is the entry barrier so high that it precludes entrepreneurial citizens or outsiders from establishing themselves?)

Tangentially, I've come to think that 'trap,' while a useful term, may be less so than 'constraint' for economic development discussion. Collier's book categorizes constraints under: conflict trap, natural resource trap, the trap of being landlocked with bad neighbors, and the bad governance trap. While these terms are proper descriptors, they are not as actionable as, say, the market access constraint. We can't do much about a nation-state being landlocked, but we can enhance market access. Or take the natural resource trap; sure it exists, but wouldn't it be more worthwhile to deal more explicitly with the specific constraints produced by these natural resources?

Read more!

Tuesday, May 20, 2008

helpin out in Burma

I recently received an update from the Buddhist Relief Mission, which is working with the Young Buddhist Student Literacy Mission, in Kolkata, West Bengal, India, a non-profit organization carrying out educational and social welfare activities, including a school and a micro-finance program aimed at women's empowerment, to supply local volunteer aid workers inside Burma:

"We purchased $6000 worth of water purification tablets, essential medicines, and canvas (at wholesale prices), translated all the instructions for the medicine into Burmese, packed everything, and sent it with two groups of travelers returning to Burma. Because of our close relationship with airport and airline officials, we were able to have all of these relief supplies transported without paying any overweight charges."

The supplies and funds have been directed to the worst-hit areas of the Irrawaddy Delta. Clearly, there is more to be done. They've said they will provide photos from the area of the volunteers in action. Please consider a quick and easy donation via Paypal through the Buddhist Relief Mission. Makes a great gift.

Words not enough to get that emotional pull of the homeless mother and son on the corner? Click here for some graphic images...

Read more!

Monday, May 19, 2008

chris matthews sounding sensible?

I certainly have my share of conservative tendencies, and often find myself agreeing with Republican policies, but I simply cannot join them (though to be fair, I often feel the same after hearing Michael Moore, et. al sound off).

Media loser Chris Matthews proves that if you give a monkey 100,000,000 hours of cable news broadcast time you'll get one Colbert-esque "nailing" moment when he takes it to a partisan hack -- in this instance, Kevin James. You see, James wanted to defend Bush's recent comments criticizing "someone's" interest in negotiating with bad guys, which Bush equated with appeasement of Hitler.

Unfortunately, while Mr. James is keen on defending on Bush's criticism of Allied appeasement in WWII and appeasement in general, Mr. James has no idea what Neville Chamberlain did , or what appeasement even means. Though to be fair, Mr. James is correct in his rebuttal that he didn't bring up the Hitler analogy (Bush did); still that isn't a very convincing argument when you remember that James has just spent the past three minutes on the broadcast yelling about the evils of appeasement, while blissfully unaware of the primary justification for dismissing appeasement as dangerous and self-defeating. This is up there with Colbert nailing the Congressman who wanted to put the 10 Commandments on public property when he couldn't even name them.

Negative points to Matthews for having this joke of a radio host on his show. Positive points to karma for nailing that annoying know-it-all moron who somehow made it "big" while being as dumb as a log. Man I hated that kid. (If I could, I'd make this post "fair and balanced" with a similar critique of the pompous ass hippie liberal, but those guys simply don't dominate the air waves in the same fashion; suffice to say, I'll be ordering an Ingrid Newkirk sandwich in a few years).

Read more!

workers are consumers, too

As the Democratic primary enters its fourth year, it’s as good as time as any to pay heed to the potential pitfalls of government intervention. Sure, it’s easy to see the appeal of the small local grocer and pharmacy over the Wal-mart behemoth. In addition, frustration with the destruction of local jobs, which has accompanied the gale of globalization and technological development, is understandable. But let us not ignore the benefits – and no, I don’t mean benefits that disproportionately benefit the most well-endowed with money and/or brains. Quite the contrary, some benefits concentrate in the lower economic strata, especially lower prices.

A recent article in the Economist documents the increasingly high cost of living in France, even when compared to (21st century) ally Germany: “A basket of identical items costs 30% more in France [than in Germany], says a study by La Tribune, a daily.” Efforts to inject greater competition into the marketplace have been stymied as “voters see competition through the eyes of producers—as a menace to jobs and factories—rather than consumers.”

Would you rather have the ~30 million Americans below the poverty line paying 30%+ for groceries to preserve the inefficient employment of a small subset of that population? The (il)logical conclusion of ‘producer preservation’ can be found in a story (lifted from Bryan Caplan article) about an economist who visits China under Mao Zedong. He sees hundreds of workers building a dam with shovels. He asks: “Why don't they use a mechanical digger?” “That would put people out of work,” replies the foreman. “Oh,” says the economist, “I thought you were making a dam. If it's jobs you want, take away their shovels and give them spoons.”

One of my favorites.

Read more!

Sunday, May 18, 2008

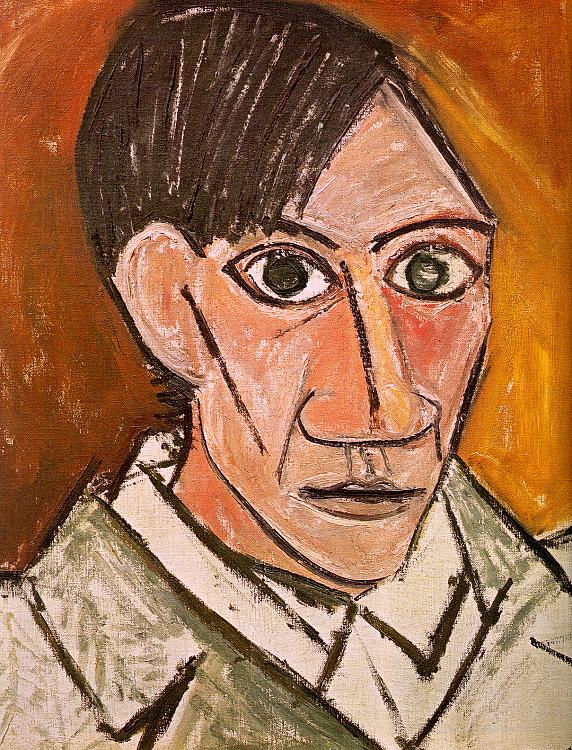

great leap forward for biblical art

He Qi's paintings conflate the biblical scenes of Michalengelo with the stylings of Picasso and the experience of a child of the Cultural Revolution. Check out his web page here and "read more" if you want to see his take on Moses' flight into Egypt and Jonah and the Whale. (Who doesn't?) If anyone wants to make me happy they can pay Qi to make me a stained glass window...

Read more!

Read more!

Wednesday, May 14, 2008

real chance for health care reform

Everyone wants to fix healthcare. McCain likes the market, but his plan for insuring those with pre-existing conditions is somewhat shoddy, and certainly doesn't put your mind at ease if you have a loved one with any sort of debilitating disease. The Dems offer two different flavors of the same lollipop, but won't offer a realistic plan for financing their operations (expiration of Bush tax cuts won't cut it). But did you know there was a reform proposal being debated in Congress that actually passed mustard as budget neutral by Congressional Budget Office? A bipartisan bill that seeks to finally move American health care beyond the employer-based model of the 20th century while upgrading the regulatory infrastructure and providing universal health care?

Sigh, if only we weren't in an election year (or had a ceaseless election cycle), the Wyden-Bennett plan would be getting more attention. Sens. Ron Wyden (D) and Bob Bennett (R) hail from Oregon and Utah, respectively, and yet found enough common ground to rehaul the American health care system:

"Under the Wyden-Bennett system, health dollars would be controlled by the individual (a long-time conservative goal) and used within a restructured, heavily regulated, totally universal, insurance marketplace."

The proposal has six Republicans and six Democrats on board, already making it "the largest bipartisan coalition ever assembled around a concrete piece of universal health-care legislation.

...

The Lewin Group, a highly respected health-care consulting firm, estimates that the plan would save $1.4 trillion over 10 years.

Unlike the proposals being bandied about now, this proposal will actually control cost to some degree -- which is *THE* problem of American health care, while still providing a "minimum standard for comprehensiveness (equivalent to the standard Blue Cross/Blue Shield plan currently offered to members of Congress), and they could not discriminate based on pre-existing conditions, occupation, genetic information, gender or age."

As you might imagine, a legitimate health care reform package is far too massive to relate in its entirety via blog post, so I will once again point you to this article on Health Care's Odd Couple. I have a few questions, but I would support its adoption tomorrow, especially if meant that none of the Presidential candidates' plans were implemented. One Health Affairs article I read directed readers to keep an eye on this proposal, as it has a better chance of being the grand plan for reform than the Presidential plans. I hope so.

Read more!

living with cognitive bias

There are few things scarier to an individual than losing the capacity to think. Alzheimer's disease is heart-breaking, as individuals' capacity to mentally engage the world drowns in increasing levels of bewildering uncertainty.

Yet few are concerned with exploring how their own brain works, and how it can be made to work better in hope of inching a few steps closer to the shore of understanding.

I haven't been particularly interested. I knew the cliches about your brain being a muscle, and agreed that even if given all the information in the world, some people just lack in mental chops. I came to equate brainpower with natural ability and hard work. I paid no regard to form -- or working "smart"-- yet anyone who has swam in a pool knows you can have all the ability in the world and splash like crazy, but your achievement depends on your understanding of how you swim.

The natural reaction is panic, an instinct as ill-suited for water as quicksand. This predisposition -- evidence of a more broad cognitive bias -- sabotages one's efforts to swim, and indeed survive.

How these cognitive biases can submarine our thinking, specifically with regards to man's efforts to help others, is the subject of this post.

The story of how I came to focus on cognitive biases may very well be case study #1920812 in their effects. After years of study (in young-people time), I began to recognize a pattern in thinking and policy that failed to heed any liberal/conservative distinction. I tried to isolate the causal variables of this mischievous pattern on the macro level, but failed. The logical disconnects (to use a term I once hated, but alas...) were everywhere.

Not the usual kind either; it wasn't the deliberate misrepresentation of facts or outright lying. It was sincere, complex, intellectual, but also, irrational. In attempting to identify the disease, I managed only to flail wildly at the symptoms, confusing one of my few readers to the point of distraction.

My dad mentioned heuristics and on exploring the topic, I came across cognitive bias. I was aware of the term, but it didn't mean much to me. On reflection, I noted that Bryan Caplan's book, "The Myth of the Rational Voter," dealt with the notion of cognitive biases. Caplan identified four biases, "anti-market, anti-foreign, pessimism, and make-work," which he contended drove individuals to vote irrationally in a systematic (and thereby destructive) manner. Caplan is interested in cognitive bias as an independent and detrimental factor in public choice.

I won't explore these biases directly, as they aren't exactly what I'm interested in. I will explore the role of cognitive biases in "doing good" (I am open to suggestion for a change in scope, however).

Cognitive biases make a boring nemesis for the do-gooder (and by extension, have seen relatively little academic treatment.) It is far more exciting to perceive of the do-gooder as an clever underdog, held back by the selfish and greedy who will one day be undone and the the do-gooder will be free to do the good deed. I will look into how the do-gooder can be his own worst enemy, and how understanding revelant cognitive biases can empower the do-gooder to do "better."

Read more!

Tuesday, May 13, 2008

NOLA -- cutting edge of education

Alex Tabarrok over at MR finds some supporting evidence for the advantage and viability of charter schools and school choice in an unexpected place - New Orleans. With little fanfare, Hurricane Katrina's destruction allowed for a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to reinvent public education.”

Alex Tabarrok over at MR finds some supporting evidence for the advantage and viability of charter schools and school choice in an unexpected place - New Orleans. With little fanfare, Hurricane Katrina's destruction allowed for a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to reinvent public education.”

"Stripped of most of its domain and financing, the Orleans Parish School Board fired all 7,500 of its teachers and support staff, effectively breaking the teachers’ union. And the Bush administration stepped in with millions of dollars for the expansion of charter schools—publicly financed but independently run schools that answer to their own boards. The result was the fastest makeover of an urban school system in American history."

The transformation hasn't turned the kids into Einsteins, but there has been demonstrable improvement in what was an entirely stagnant school district.

"Classes are smaller, many of the teachers are youthful imports brought in by groups like Teach for America, principals have been reshuffled or removed, school-hours remedial programs have been intensified, and after-school programs to help students increased... Mr. Vallas attributed many of the improvements in testing to the new teachers. 'The biggest contributing factor was the quality of the instructors,' he said."

A commenter at MR gets at the crux of the issue:

"Smaller classes. Young, energetic teachers. More remedial programs. More after-school programs. Can't government do this? If the answer is no, why not? If the answer is yes, why hasn't it?"

Those are very fair questions for both sides of the private/public debate. I think the government cannot be relied on to do this because education, especially to low-income kids, is too dynamic for top-down management. No Child Left Behind has highlighted the difficulty in top-down accountability, and the low reported results demonstrate that we have not figured out how to relay even the basic concepts needed for success.

There's a lot of experimentation that needs to be done. Teachers and principals need the flexibility to try different programs, allocate resources differently -- in short, to innovate. There will be success and failure in this process.

I think government programs are ill-suited to support this process, as they are vertically-structured organizations that manage local institutions by ensuring they comply with certain processes, curricula, standards of practice, etc. They inherently stifle innovation and create incentives to stick to established practices, even when the established practice is not providing acceptable results to a large number of students.

I don't think it's necessarily impossible for any government managed school to be innovative or successful. The government (likely state level) might introduce market concepts (increase flexibility and accountability for principals, school choice, etc.) into the government-owned system; this artificial environment could certainly be better than what we have now.

Still, the artificial dynamism will never reproduce the dynamism of the actual market. Just as I would rather hire a consultant to teach me how to improve my business, I would rather have a professional, than a bureaucrat, in charge of teaching my kid how to write complete thoughts. If you don't like how they're doing, you can always hire a different one.

Read more!

Sunday, May 11, 2008

value of military intervention

Paul Collier is back again with cost-benefit analysis of foreign aid and military invention in conflict areas. The short story is that foreign aid and military intervention can and indeed usually do reduce bloodshed around the world. The invasion of a centrally-controlled and ordered Iraq, Collier notes, is not representative of the usual efficiency and effectiveness of such engagements; "the far more typical scenario is political violence within a small, low-income, low-growth nation burdened with strong ethnic divisions." Even still, aid is less cost effective than the use of peacekeeping forces: “Compared with no deployment, spending $100 million on a peacekeeping initiative reduces the ten-year risk of conflict from around 38% to 16.5%. At $200 million per year, the risk falls further, to around 12.8%. At $500 million, it goes down to 9%, and at $850 million drops to 7.3%.” This does not include the conflict abatement that occurs because the belligerents know that well-armed, well-trained troops will be dispatched if they are to act violently. To that end, Collier recommends “an “over the horizon” security guarantee: a reliable commitment to dispatch troops if they are needed. A guarantee could be offered by the UN or a regional power like the African Union to protect governments that came to power through certified democratic elections.” Collier believes that such “a guarantee could credibly help the world avoid three of the four new civil wars expected in low-income countries in each decade.” What would the cost be for a capable security force? Around $2 billion annually. And the benefits? Collier argues that the returns on the “significant reduction in the risk of conflict and faster economic growth are between 11.5 and 39 times higher.” Not a bad investment. Collier concludes by providing an overview of a general strategy for helping nations escape the conflict trap, which I would endorse without question: “Combine aid, limits on military spending, peacekeeping forces, and “over the horizon” security guarantees in a way that ensures that the developed world deals with hot spots consistently. The UN Peace-Building Commission has the potential to coordinate this. The annual cost of the full package would be $10.8 billion, but the benefits to the world would be at least five times higher.” The problem is no one, but the US (for all its problems), has shown much of a commitment to aid with this public good.

Collier begins by arguing that conditions prohibiting military spending of aid packages by host countries is important, as "about 11% of all aid is currently diverted into military spending, which significantly increases the likelihood of violence." The reduction in risk and increase in discretionary cash would allow benefits from aid to more than quadruple costs.

Saturday, May 10, 2008

what to do in myanmar?

I remember speaking with some German friends a few years back about just war and objecting to their characterization of ALL military engagements as inherently unjust. The context was the war in Iraq, but we weren't discussing the wisdom of the invasion or the objective virtue of that particular engagement, but the potential for war to be just.

My stock scenario is the genocidal regime, which most people I talk to seem to agree justify the consideration of military intervention (the decision to actually intervene should also take into account the likelihood of success and potential fallout).

Romesh Ratnesar, over at Time, raises another scenario that might pass mustard with the peacenik crowd, or at the very least, make them acknowledge the terrific human loss that their international consensus politics and soft power allow to occur quite regularly. Ratnesar poses the question, "Is It Time to Invade Burma?"

I would rephrase the question; does the crisis in Burma warrant the consideration of military force to alleviate the crisis if need be? A less-appealing headline to be sure, but a bit more useful for our purposes.

Here are some relevant snippets from the article:

Is there a difference in allowing hundreds of thousands to die from disease and hunger and outright execution? In some ways, yes, just as first degree murder differs from second and third. What is consistent in both cases is the preventable loss of human life.

Members of the international community have stated multiple times that state sovereignty extends only as far as the state's willingness (and I would add ability) to protect its people from preventable death.

The issue is that these pronouncements carry little weight. Soft power (which usually ends up meaning economic bullying) works very well for certain types of regimes, but incentives have their limits.

I'm not advocating military intervention in Myanmar. I am suggesting that you don't have to be a neocon to believe that the international community's ability to act through existing international institutions to alleviate large-scale human suffering and death is basically non existent, and it is unacceptable to allow these preventable real human tragedies to occur because of abstract notions of state sovereignty (I'd love to hear someone, anyone, argue that the Burmese junta represent the people) or international consensus (couldn't avoid a security council veto short of an alien invasion). We should reinforce the processes of international cooperation when possible and respect the people's right to self-determination, but we mustn't join our European friends in sacrificing the lives of others at the altars of multilateralism and state sovereignty.

Read more!

Thursday, May 8, 2008

what jane jacobs can teach us: borders

Jane Jacobs wrote the book on city planning for the latter half of the 21st century, and it's yours for a little more than $10 at Amazon -- The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Need more convincing? Dead End or Hub? Border areas suffer from a lack of land use and circulation of people, which stimulate local growth and safety. Intensity is low because border areas are the last stops on the line, dead ends that inhibit individuals from traversing across the border area. These border areas suffer from "fewer users, with fewer different purposes and destinations at hand," creating vacuums that are typically unproductive and unsafe. Some borders allow traffic one-way (Arizona/Mexico), others see traffic, but only at certain times, but the effect is the same. Border areas are best served by making the border a "seam rather than a barrier, a line of exchange along which two areas are sewn together." It's not that border areas, or frontiers, are prone to blight and disuse. To the contrary, frontier areas are positioned to be uniquely original and creative thanks to cross-border exchange and ability to escape potentially crippling central oversight. Jacobs' insight is that the border areas have their fate in their own hands, at least to some degree. They can fade into disuse and disrepair as the last building in the dead end, or they can serve as a hub for interaction between both sides of the border. The potential for these areas cannot be overstated -- frontier cities are often the centers of the next empires. Historically, commerce, exchange, and the free flow of ideas and goods have been the keys. Claustrophobic borders Some areas are large enough and diverse enough to be productive and vibrant despite being cutoff by a border (though the smaller area specifically near the border won't be vibrant), but it becomes increasingly problematic when the neighborhood is too small to support itself as a district. This merries well with the literature I've seen with regards to small nation-states -- too small to support the diverse commerce needed -- damned to exist as fragments by borders which inhibit the pooling of human and financial resources needed to grow. What if Rhode Island had its own currency, tariffs and regulated employment visas for other states in 1960? Well, if you add in a bunch of poor, violent neighbors and make our little state a land-locked country with no history of effective governance and scarce resources you'd have Burundi, with a GNP per capita of about $90. Would the dissolution of borders make Burundi the center of an African superpower? Likely not, but it does serve as a barrier to the the accumulation of capital -- financial and human -- needed to escape the poverty trap. Minor internal borders as wasteful barriers Jacobs has additional insights into man-made barriers that lead to dullness and blight, which I think are worth noting. She focuses on single elements with low intensity land use, such as civic centers, large medical centers, large parks, and universities. She reserves special criticism for universities, which orient inwards, completely disengaged from their surroundings, producing a deadness to all that borders them. She looks at Central Park and notes that the area goes nearly unused at night; it features many attractions like carousels buried deep inside, which should be pushed to the border with the city, to allow for greater utility. The challenge is to minimize these large single-use areas, or at least pack them near multi-use, high-concentration areas that can overcome the single-use area's deadening externalities. City planning misconceptions have even taken some positive city features, like waterfronts and parks, and made them dull, by insisting on single uses that serve only small segments of the populations at specific times -- making the areas dull and even unsafe at other times. Next to you are walking around a city, pay attention to the buildings around you and how they are used; do they serve multiple uses, populations? Do the buildings use throughout the day, or only at specific times? Are there large single-use facilities? Are the blocks small or large (I'll have to return to this later)? By what visual cues do you segment the city? Jacobs packs a lot of insight to both shape how you understand the world around you and how the city around you is shaping your perception, habits, and opportunities.

Jacobs has a little something for everyone, whether you're interested in learning about why a neighborhood is hip or dull, slums improve or decline, your university's neighborhood was so boring, border towns are wastelands, automobiles are so problematic yet important, visual perception affects city life, city planning and public spending failed miserably, different processes of scientific thought shape city policy, the role of economic development in city formation, and/or the role of city formation on economic development. (Exhale)

I'll have a series of posts bringing out some of her broader points that I think are applicable to not only cities, but economic development at home and abroad. First up, is Jacobs' treatment of borders, which for the most part refers to borders between towns, but I find quite applicable to most borders.

maximize your ROI on social investment

One of the concepts I often explore is how one most positively impacts the world given their scarce amount of personal resources. If you've read any past posts, you've noted that I've downplayed domestic policies' importance, and stressed more abject suffering abroad.

The death toll in Myanmar numbers in the tens of thousands, and will likely take many more lives in the future due to famine and disease. If you have no problem supporting relatively-well off Americans, I'd ask you to consider donating to disaster relief. Outside the incredible need in the devastated area, disaster relief is also more likely to make a positive impact than money spent in social programs, because it's much easier and cheaper to solve the problem of not having a roof with short-term assistance, than it is to fix behavioral problems through long-term subsidization of sub-standard living. Assistance following a disaster should be considered preventative care, to ward off the harbingers of disease and famine that accompany such destruction. Workable land and drinkable water are worthy, doable aims.

Bottom line, your dollar goes a lot farther to people who need it a lot more. Of course, this immense amount of suffering only underscores the despicable depth to which Myanmar's military regime has sunk. Even France wants to trample on their sovereignty... but alas, we wait on the UN for the OK. I wish we could see statistics for death by red tape.

You can do a small part, by donating to the Buddhist Relief Mission, which works in the area. The question with these organizations is always whether the money is actually being directed to the intended cause. I suggest the Buddhist Relief Mission based on the recommendation of Yale economic development professor Chris Blattman.

Blattman has ties to the area, namely friends who run a community program for Burmese refugees in Thailand, and they recommend the Buddhist Relief Mission. Blattman also points to a list of international aid agencies in the NY Times, if you want to play it safe.

Read more!

Monday, May 5, 2008

hillary makes play for stupid, selfish vote

Hillary Clinton's campaign has clearly segmented the voters and focused on the population who likes to whine about energy prices and will embrace any plan, no matter how inane.

UPDATE: Hoping for that last-second push in Indiana, Hillary busted out this gem at a minor-league baseball stadium, “We're going to knock balls out of the country's park, for the home team, which is America."

There are no typos in that sentence.

Credit must go to John McCain for getting the ball rolling on this stinker, but Hillary gets big points for not only supporting a stupid idea, but digging in against the entire economics profession when asked why her proposal could not find one_single_economist to endorse it: "I'm not going to put my lot in with economists. ... We've got to get out of this mind-set where somehow elite opinion is always on the side of doing things that really disadvantage the vast majority of Americans."

Apparently, Hillary is going with her gut on this own instead of listening to high-minded, so-called experts, with their "facts" and "years of study." Remind you of anyone?

As Arnold Kling wrote, "Soon I expect to hear the Senator from New York promise to jump out of a tenth-story window and fly, to demonstrate defiance of "elite" physicists who doubt the feasibility of the project. "

Read more!

Sunday, May 4, 2008

the rise of the rest

Fareed Zakaria is back on Newsweek with a feature-length version of his upcoming book, "The Post-American World." Zakaria's piece is largely optimistic about the world at-large, but that doesn't mean he overlooks its problems -- he simply places these concerns in their proper context -- and advises the world's actors -- namely the US -- on how to best advance their interests.

Americans aren't quite sold on Zakaria's story of shared prosperity, as Zakaria quotes a figure of 81% of Americans believing the country is on the "wrong track." He argues that while the financial panic, war in Iraq, and terrorism are the hot topics of the day, Americans are actually disoriented by the greater changes at work -- the tallest building is in Taipei, biggest refinery is in India, largest passenger airplane is built in Europe, biggest movie industry is in Bollywood, etc.

Intellectuals wax about the 'decline' of the United States. An upcoming book asks if America is to follow the self-destructive path of the Roman Empire.

This is a sexy story, as there are certainly plenty of savory, superficial parallels between the US and fallen powers of the past.

Zakaria provides a different -- less American-centric -- narrative about the "rise of the rest," complete with insights into what the next steps are for global prosperity and American competitiveness.

Below, I will excerpt liberally from Zakaria's piece to skip to the juicy parts:

Rise of the Rest

Remaining Challenges

The US still has a lot going for it...

Secret to American success

Challenge to the US

My takeaways are the importance of cutting the fat of the American economy, embracing talented, hard-working immigrants from other countries, continuing our higher-education dominance, and acknowledging the multi-polar world we have helped to create.

So far the story of the 21st century is the "rise of the rest," whether it is also the decline of the US depends on us.

Read more!

Saturday, May 3, 2008

the food crisis explained

The Financial Times features some of the best economists and political scientists in the world, and recently, it's been the universally-celebrated Paul Collier talking sense in their Economists' forum. One of my first posts lauded Collier's terrific analysis of global poverty and general strife in his book, The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries are Failing and What Can Be Done About It." (Link to Amazon).

Collier is back once again to explain the why there is a food crisis, what stands in the way of an adequate food supply, and what should be done about it. (Hat tip: Alex T at MR)

First, Collier explains the why:

"Why have food prices rocketed? Paradoxically, this squeeze on the poorest has come about as a result of the success of globalization in reducing world poverty. As China develops, helped by its massive exports to our markets, millions of Chinese households have started to eat better. Better means not just more food but more meat, the new luxury. But to produce a kilo of meat takes six kilos of grain. Livestock reared for meat to be consumed in Asia are now eating the grain that would previously have been eaten by the African poor."

Next up, a realistic solution:

"The remedy to high food prices is to increase food supply, something that is entirely feasible. The most realistic way to raise global supply is to replicate the Brazilian model of large, technologically sophisticated agro-companies supplying for the world market."

But, of course, there is a catch:

"Unfortunately, large-scale commercial agriculture is unromantic ... We laud the production style of the peasant: environmentally sustainable and human in scale."

Collier notes that we grew out of this perception of manufacturing (who dreams of owning a small manufacturing "ranch"?), and have enjoyed the manufacturing wealth since.

Yet this romanticism has taken root in agricultural development:

"In Africa, which cannot afford them, development agencies have oriented their entire efforts on agricultural development to peasant style production. As a result, Africa has less large-scale commercial agriculture than it had fifty years ago. Unfortunately, peasant farming is generally not well-suited to innovation and investment: the result has been that African agriculture has fallen further and further behind the advancing productivity frontier of the globalized commercial model."

In case you thought it couldn't get worse, Africa is the victim of more than one breed of romanticism:

"Our longstanding agricultural romanticism has been compounded by our new-found environmental romanticism. In the United States fears of climate change have been manipulated by shrewd interests to produce grotesquely inefficient subsidies for bio-fuel. Around a third of American grain production has rapidly been diverted into energy production."

Collier also reserves some blame for the European Commission, which has its own bio-fuels policy, albeit less "effective" and thereby less damaging. More damning is the EU's ban on the "production and import of genetically modified crops has obviously retarded productivity growth in European agriculture: again, the best that can be said of it is that we are rich enough to afford such folly. But Europe is a major agricultural producer, so the cumulative consequence of this reduction in the growth of productivity has most surely rebounded onto world food markets. Further, and most cruelly, as an unintended side-effect the ban has terrified African governments into themselves banning genetic modification in case by growing modified crops they would permanently be shut out of selling to European markets."

But wait, there is one more nail in the coffin for food supply. Export-restrictions in grain-exporting countries, a product of "the internal tussles between the interests of poor consumers and poor producers, the interests of consumers have prevailed. Governments in grain-exporting countries have swung prices in favour of their consumers and against their farmers by banning exports."

The effect is that grain-exporting countries have lower prices, but less grain is produced than would otherwise be produced, reducing the overall food supply, and greatly raising the prices for grain-importing countries.

What's the main takeaway?

"Unfortunately, trade in agriculture has been the main economic activity to have resisted being subject to global rules. We need stronger and fairer globalization, not less of it."

I like this piece for a few reasons -- it's comprehensive, it's straightforward -- but I especially take note of Collier's condemnation of romanticism. It's similar to what I've been trying to get at in the "moralizing" series of posts, and it demonstrates the shallowness of thinking on the left as well as the right. I'm reading Jane Jacobs' "Death and Life of Great American Cities" right now, and she strikes me a similar thinker, one who is able to see the err of well-intentioned, but entirely unintellectual pursuits.

Read more!